Seeing Chromatin Scaling with Cell Size, from Interphase to Mitosis

Posted by Manuel Mendoza, on 26 January 2026

Melike Lakadamyali, Jérôme Solon and Manuel Mendoza

As cells divide during development, their size evolves dramatically while DNA content remains constant. This raises a fundamental question: does chromosome compaction adjust to these size changes so that genomes are still segregated faithfully? This question has been with us for a long time. More than a decade ago, one of us (Manuel) published a paper with Yves Barral and colleagues showing that in budding yeast, mitotic chromatin compaction scales with spindle size (1). That work suggested that chromosome architecture somehow adapts to cell geometry. We wanted to know if, similar to yeast, chromosome compaction adjusts to cell size in metazoan cells – where arguably the need to adjust is more relevant, because of changes of cell size during development.

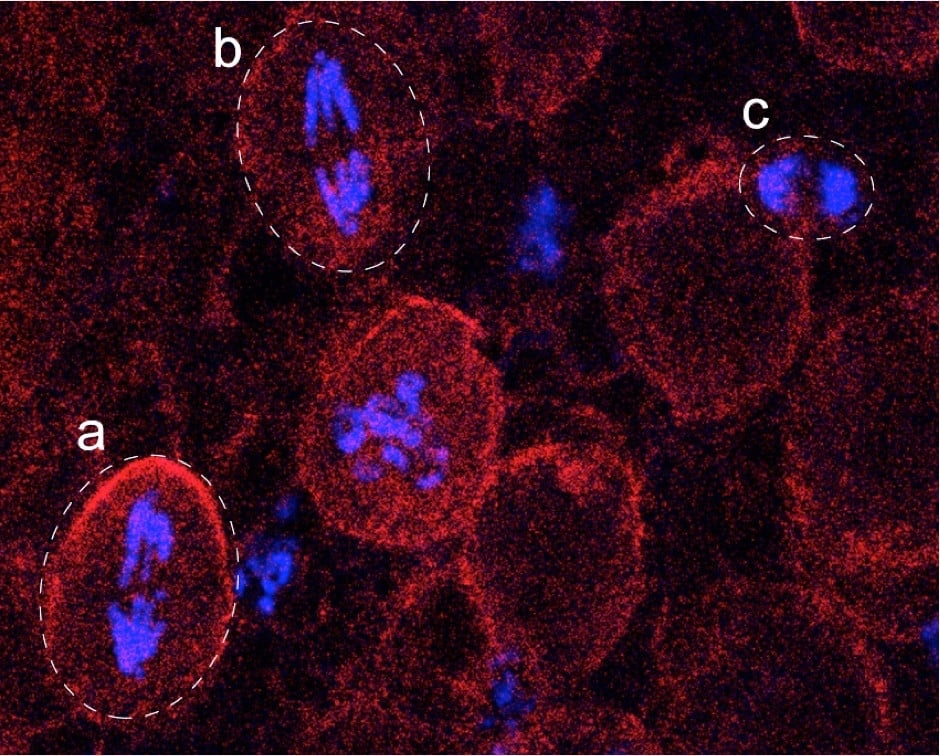

An ideal system to study this is the Drosophila nervous system (Figure 1): large neural stem cells, or neuroblasts, divide asymmetrically to generate much smaller ganglion mother cells (GMCs), much like yeast mother cells produce smaller daughters. The project was born at the CRG in Barcelona, where the lab of Jérôme, who is an expert in Drosophila development, sat next door to Manuel’s, with postdoc Petra Stockinger leading the work. In the meantime, studies in worms and frogs had shown that chromosome compaction during mitosis is somehow proportional to the size of the nucleus in interphase (2–4). But how does nuclear volume influence DNA density before cells even enter mitosis? Addressing this experimentally is challenging, because chromatin is so densely packed that conventional light microscopy struggles to resolve its organisation at the relevant length scales.

Representative fluorescence image showing chromatin (phosphorylated histone H3, blue) and cell outline/cytoplasm (Miranda, red). Dashed outlines indicate individual cells. (a,b) Neuroblasts (NBs), large cells displaying proportionally large mitotic chromosomes, illustrating scaling of chromosome size with cell size. (c) Ganglion mother cell (GMC), markedly smaller in size, with hypercondensed mitotic chromosomes that are scaled down accordingly. This comparison highlights how chromosome compaction adapts to cell size to ensure faithful genome segregation. Image courtesy of Zhanna Shcheprova.

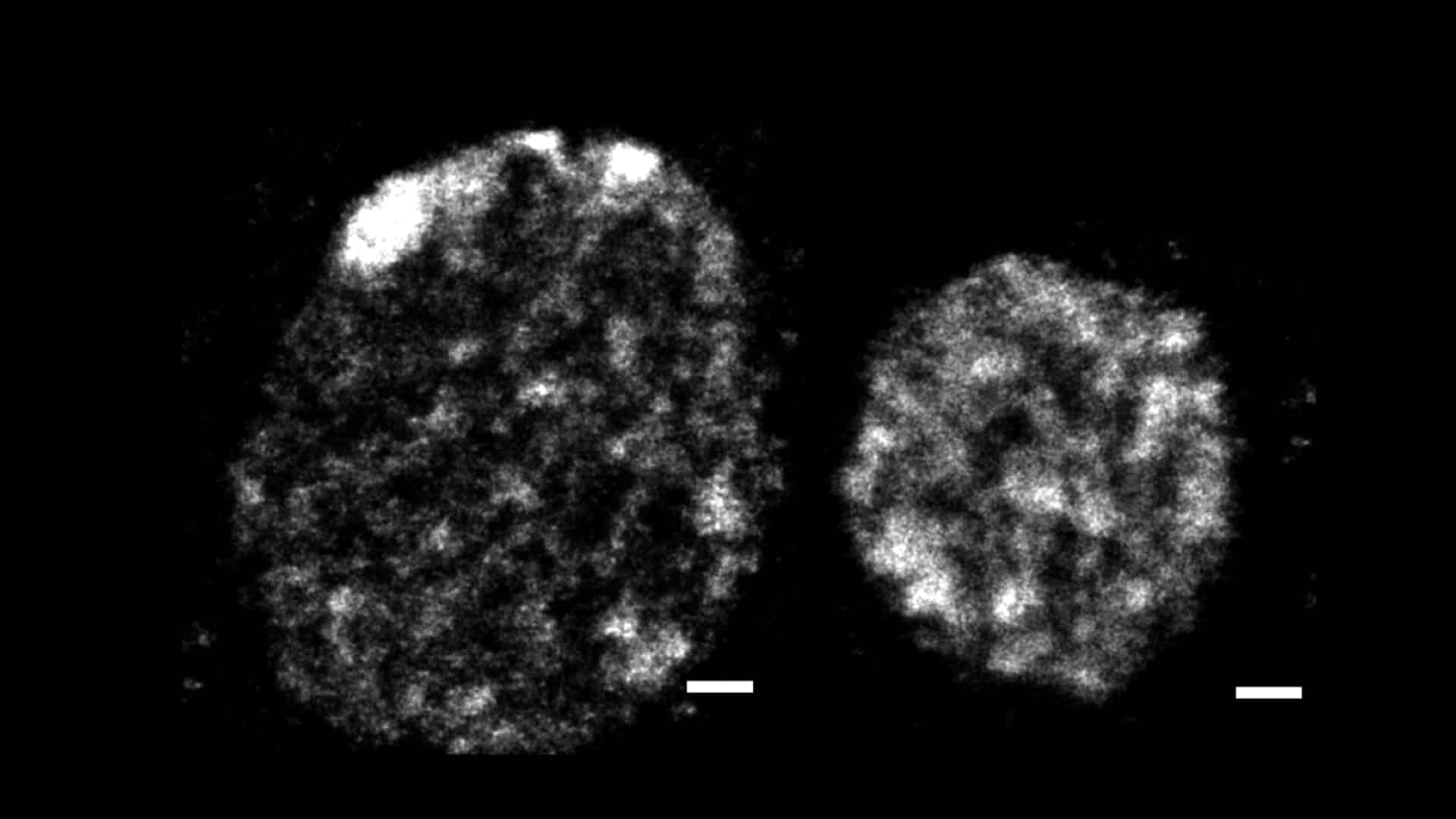

To overcome this limitation, higher resolution was needed, but probing interphase chromatin structure at the nanoscale required expertise Manuel’s and Jérôme’s labs did not have. That expertise was right next door again, at ICFO, where Melike and her postdoc Anna Oddone had developed powerful super-resolution approaches to study chromatin organisation. The full consortium then turned to super-resolution STORM microscopy. Using 3D STORM imaging combined with Voronoi tessellation analysis, we generated detailed spatial maps of DNA organisation inside interphase nuclei (Figure 2). Working in Drosophila neuroblasts and GMCs, which naturally span a wide size range, we found that nanoscale chromatin density follows a clear power-law relationship with nuclear volume. As a result, larger nuclei contain less compact chromatin and extensive chromatin-poor regions, whereas in smaller nuclei chromatin is more compact and occupies most of the nuclear volume.

Representative 3D STORM image of chromatin in interphase nuclei of a large NB (left) and a smaller GMC (right), visualised by labelling DNA (EdU). Local variations in chromatin density are apparent at the nanoscale, revealing a heterogeneous organisation rather than a uniform DNA distribution. Scale bars, 500 nm.

Importantly, this scaling reflects molecular regulation rather than mere physical packing. When we blocked histone deacetylase activity, the precise power-law relationship broke down and shifted toward a much more linear dependence. This showed that chromatin scaling is actively controlled, likely through changes in chromatin–chromatin interactions, rather than being a passive consequence of squeezing DNA into a bigger or smaller space.

To extend our interphase findings into mitosis, we needed a way to quantify chromatin compaction dynamically in live cells. Traditional segmentation-based approaches are difficult to implement during mitosis because fluorescence intensities are unevenly distributed and change dramatically. To bypass these limitations, we developed a novel method which exploits the fact that freely diffusing histones and chromatin-bound histones follow distinct fluorescence intensity distributions. This allowed us to quantify chromatin volume of chromatin-bound histones without relying on arbitrary thresholds, and to track compaction dynamics live.

Using this approach, we found that power-law scaling persists into mitosis, although the scaling exponent decreases. This indicates a shift in chromatin behaviour during mitotic compaction, consistent with a transition in the underlying polymer state, which is probably linked to phase separation–like dynamics. Crucially, this provides a physical explanation for how memory of interphase chromatin organisation is carried over into mitosis (5).

Why does this matter? During development, cells divide across a wide range of sizes, yet accurate genome segregation must be error-free even in the smallest of cells. Scaling provides a robust solution to this problem. Our results indicate that interphase chromatin architecture dynamically adjusts to the size of the nucleus, and is linked to appropriate mitotic compaction, ensuring faithful genome segregation across diverse developmental contexts.

From an imaging standpoint, an important aspect of this work is the way it bridges scales. Super-resolution STORM allowed us to quantify nanoscale chromatin density in interphase nuclei, while live confocal imaging made it possible to follow chromatin compaction dynamics through mitosis in real time. Individually, neither approach would have been sufficient: STORM provides exquisite spatial detail but only static snapshots, whereas live imaging captures dynamics but lacks nanoscale resolution. By combining the two, we were able to construct an integrative view of chromatin scaling that spans from interphase organisation to mitotic compaction. Looking forward, a major challenge will be to connect this multiscale imaging framework with molecular biology approaches, to understand how the “memory” of the interphase chromatin state is physically transmitted into mitosis. One intriguing possibility is that condensin-dependent loop formation is tuned by interphase chromatin density, such that differences in nanoscale packing bias how loops are generated and stabilised during mitosis. Integrating super-resolution imaging, live-cell dynamics, and molecular perturbations will be essential to move from scaling laws to mechanisms.

References

1. Neurohr, G., Naegeli, A., Titos, I., Theler, D., Greber, B., Díez, J., Gabaldón, T., Mendoza, M. & Barral, Y. A midzone-based ruler adjusts chromosome compaction to anaphase spindle length. Science 332, 465–468 (2011).

2. Hara, Y., Iwabuchi, M., Ohsumi, K. & Kimura, A. Intranuclear DNA Density Affects Chromosome Condensation in Metazoans. Mol. Biol. Cell (2013).

3. Ladouceur, A.-M., Dorn, J. F. & Maddox, P. S. Mitotic chromosome length scales in response to both cell and nuclear size. J. Cell Biol. 209, 645–651 (2015).

4. Kieserman, E. K. & Heald, R. Mitotic chromosome size scaling in Xenopus. Cell Cycle 10, 3863–3870 (2011).

5. Stockinger, P., Oddone, A., Lakadamyali, M., Mendoza, M. & Solon, J. Chromatin compaction scaling with cell size follows a power law from interphase through mitosis. Biophys. J. 124, 3678–3689 (2025).

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)